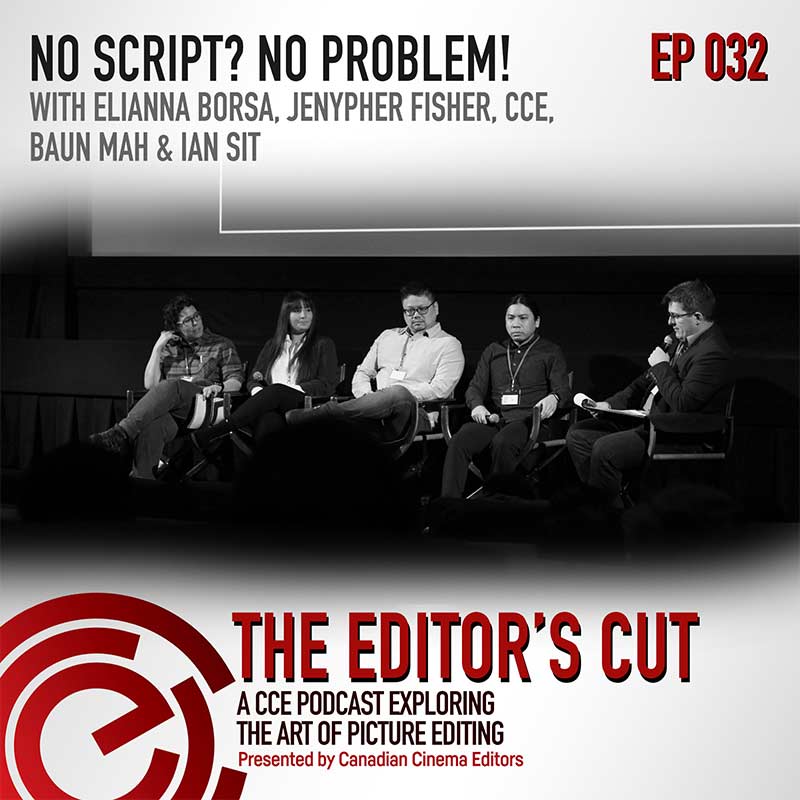

The Editor?s Cut – Episode 032 – ?No Script, No Problem? (EditCon 2020 Series)

Sarah Taylor:

This episode was generously sponsored by Blackmagic Design. Hello and welcome to The Editor’s Cut. I’m your host, Sarah Taylor. Today, I bring you part one of our four-part series covering EditCon 2020 that took place on Saturday, February 1st, 2020, at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto.

Massive hours of footage, tight deadlines, and no script? No problem. Editors from hit shows including Big Brother, The Amazing Race, Yukon Gold, and In the Making show how they got to the finish line. Featuring clips from these and other top-rated and award-winning reality and factual programs, this discussion breaks down the process of cutting unscripted programming both creatively and technically.

[show open]

Simone Smith:

Good morning, everyone. So we’re going to jump right in this morning with an inside scoop into the people who mine hours of footage to find the gems.

Simone Smith:

With experience in unscripted shows of all types, the Amazing Race Canada and Big Brother Canada to the nature of things and artist profiles in In the Making, our moderator is industry veteran Jonathan Dowler. Jonathan’s credits include Big Brother, So You Think You Can Dance, Master Chef, and the Amazing Race Canada. He is a 12 time CSA and 15 time CCE nominated editor, and has won five consecutive CSAs and four CCE awards.

Simone Smith:

Blackmagic Design are pleased to welcome editors Jonathan Dowler, Baun Mah, Elianna Borsa, Jenypher Fisher, and Ian Sit.

Jonathan Dowler:

We’re going to just dive right in. Unscripted is covering everything, from reality competition shows to factual entertainment, which could be hewed slightly from, I guess, docu-dramas or series docs and goes straight into unscripted. So you can have everything.

Jonathan Dowler:

Just to give you a little background, in this boom of TV that’s called the Golden Age, but shouldn’t be forgotten amongst all the scripted programs that unscripted is having banner years one after the other. And it’s proliferating the industry. Just in an outdated industry report, $300 million in the Canadian economy has come from unscripted programming, from formatted shows, and it is getting rave reviews. Amazing Race Canada is one of the highest rated shows in Canada every season, and many people tune in to see everything from house guests to chefs to artists to dancers, singers.

Jonathan Dowler:

So we’re here to talk about some of the experts and their experiences, because the challenges of this genre are incredible. You are given so much footage. What you don’t have in a script you have in footage that will help you forge the story, and arguably one could say that the story, more than any other format, is forged in the editing suites.

Jonathan Dowler:

So here we are. We’re going to talk about tips and tricks.

Jonathan Dowler:

First off, the majority of students coming out of colleges or universities, film schools, might get their start in unscripted. That being said, I just want to go down the line, and just see just a very quick intro of how you guys got into editing and to your first jobs in the industry.

Jonathan Dowler:

So, Jennifer, why don’t we start with you? Start down the line.

Jenypher Fisher:

Sure. Oh, it works. Great. That’s fantastic. If we’re a little nervous, I think it’s understandable. We usually hide in rooms. We don’t come outside rooms. We don’t speak in public, except if we blow up. We go back and hide again. So forgive us, at least me, because I’m nervous.

Jenypher Fisher:

I’m from Vancouver. I went to BCIT, which is a technical institute, because I couldn’t afford to go to film school. It was a lot of money. Technically, I got trained in news editing, which I had zero interest in doing, but it was a good way to get into the industry. I had, honestly, it was a two year program. Year one, it was tape-to-tape editing, because I’m kind of old. And I had no interest in that. Like, zero. I was like, this is great, it’s fine, but nothing.

Jenypher Fisher:

Second year of BCIT, the Avid showed up, and I went, ah, that. That is the way that I … Suddenly, it seemed like a thing I wanted to do, and no one knew how to use it, so I trained myself on it. Then I trained the teachers, then I trained my other students, then I trained the first-years, and then I went and got a job. And that’s pretty much how I got into editing.

Jenypher Fisher:

And, actually, the other thing is I remember right after the Avid came, I decided I knew I was going to be a shooter or an editor. One of these two things was going to happen, and I decided that shooting was a little too stressful, because you could really fuck it up. You could really, really screw people by not getting the right shots, by tinting it blue, by whatever. And editors could just save things, which is not true. We can screw it up, but seemed to me at the time to be completely true, and that’s why I chose editing because I have a need to fix things.

Elianna Borsa:

When I was a PA on set, I wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted to do, and I just asked a lady for some advice, and she said get into either pre-production or post-production because they’re the longest contracts. And I didn’t like paperwork, so I’m like, okay, I’m going to try post-production. And I did like editing in school, and from an internship, went into the post-production department, and I was working as an assistant. And then I kind of just put myself out there to edit some webisodes and just some stuff that the network would see. And then from there, it’s just I had a really awesome post producer. She was great, and she was very willing to help assistants. That’s Angie Pajek. So she was like, “Let her do more things. Let her do more things.” And then from there, I quickly became … I’m a junior editor on the Cold Water Cowboys, and then about two months later was editing, and it’s kind of just gone from there.

Baun Mah:

Yeah. I started out doing the typical Asian son thing and trying to become a doctor. In third year, I realized I was going to fail at that, so I started taking some arts courses because I’ve always been interested in photography, visual arts. And then I took a film course in my fourth year, and that sort of sparked it, the beginning of my love for film. And then so once I graduated, I had the choice of either becoming a lab assistant or doing research for the rest of my life, or try again and have a hand in film.

Baun Mah:

So I applied at Ryerson. I got into the Ryerson Image Arts program. I did four years there. Ended up loving it, and, yeah, I also did a little bit of camerawork. Super stressful. This body is not made to stand for like 10 hours, so I gravitated towards the chair, which went into editing.

Jenypher Fisher:

Sitting is good.

Baun Mah:

Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

Standing is better.

Baun Mah:

And then from there, after I graduated, I did sort of smaller jobs here and there. I … not really assisted, but I was like a web content editor for a Discovery series called Diamond Road, which was a really great series. One of Jennifer’s coworkers, Andy Bailey, actually trained me how to use Final Cut, because I was an Adobe Premier guy.

Baun Mah:

And then from there, I just kind of sort of dabbled in documentary, smaller documentaries for local channels. And then my big break was getting the editing job for the Gemini Awards, which is now known as the Canadian Screen Awards. And from there, I’d met some producers who got me in touch with Insight, and they happen to do a lot of the bigger reality shows here in Canada. And it’s been nine years from that.

Ian Sit:

I also didn’t go to film school. It was a sort of Asian son thing as well. I studied economics, and I got a degree in commerce at U of T. But then I had no intention on becoming an economist ever. I always knew that I wanted to try something in film, so after that, I taught myself how to edit. At the time, it was Final Cut Pro 7. That was the easiest software to get your hands on.

Ian Sit:

Then a couple of years of just doing anything, saying yes to everything. Not getting paid for any of these jobs until one day on Facebook someone posted a job posting for an assistant editor job for a travel food show, and it seemed very urgent. And I just so happened to be the first guy, because you can see the time thing. It’s like two minutes posting. So I immediately replied, and it was urgent. By the end of the day, I was at Technicolor doing assisting editing work for this travel food show.

Ian Sit:

And then from there, I guess I made a good impression, got recommended for more jobs, and then just grinded it out for several years before I became a full editor.

Jonathan Dowler:

All right. Now we’re all here in the landscape of unscripted, and I think we had a discussion when we first met up, and it was “no script, no problem.” And, Ian, what did you have to say about “no script, no problem?”

Ian Sit:

I said you should change it to “no script, a lot a lot of problems.” Super many problems.

Jonathan Dowler:

Yeah and it’s just … Problem solvers. That’s what we are in unscripted, because when you say “unscripted,” does that mean that there’s no plan, and where we figure into it? So I guess the question would be what is your average workflow for someone who might know what unscripted, how that flow works? We’ll just talk about factual elements. And I want to talk about factual entertainment. You can think of reality competitions as whenever someone’s singing to win, on a race to win, trying to win in a household competition. But when we talk factual, it could be something that’s more storyline based such as Cold Water Cowboys, the Deadliest Catch, all the way down to, if you’re going to the other end of the spectrum, which is the Kardashians or other ones which are long form stories that take place over the course of a season.

Jonathan Dowler:

So let’s talk about unscripted factual, and basically Jennifer and Ian, give us … Why don’t we say, Jennifer, you’ve worked on Jade Fever.

Jenypher Fisher:

Yeah.

Jonathan Dowler:

Let’s just talk about perfect scenario and then we’ll talk about what actually happens, but in terms of no script, what do you get in the form of story in terms of footage? What do you get?

Jenypher Fisher:

What do I get? For Jade Fever, current is a half an hour show. It’s about Jade, a lovely green rock that people apparently want. I don’t understand, but that’s fine. We have two writers on the show. We have a showrunner and a writer, and that’s it. And we have two finishing editors. I’m one of them, but I also do my own rough cuts, and I think we’ve had three other editors.

Jenypher Fisher:

Generally, the workflow is the editor who is doing the rough cut … We call it the internal rough cut. It gets four weeks. You get a string-out from a writer. Now, a string-out could be anything from 40 minutes. Keep in mind, that’s a 22 minute show. 40 minutes of general thoughts, “Here’s what I think is going to happen.” It could be great. It could be crap. It doesn’t really matter. Either way, you’ve got to deliver a show at the end. Jade Fever is actually pretty good. It’s well thought out.

Jenypher Fisher:

My last string-out was two hours long for a 22 minute show, so that was a lot. I still have the same 10 days to get it to basically an assembly. So I take 10 days, which generally comes out to I have to conquer two scenes a day every day. At the end of 10 days, I have a general assembly. It’s not great, but it generally shows the picture of what the show will be. At that point, we all sit down. That’s me, the writer, and the showrunner, and maybe the in-house executive, and we basically look at it and go, okay, this works, that doesn’t work. Fix that.

Jenypher Fisher:

Then you’ve got two more weeks with the writer. Oh, I forgot to mention. The first two weeks, it’s just me. There’s no writer. It’s I’m in charge of everything. I’m in charge of the VO, which I write badly, but it’s there. I’m in charge of basically crafting the entire thing. Second two weeks, I actually get a writer. We hammer it out. We try to make it look good. We put music on it, and then it goes to a finishing editor, which is also me in this case, and because I’m the assembly editor, they give me one week instead of two because my assembly is supposed to be better than everyone else’s. It’s not fair, but that’s fine.

Jenypher Fisher:

So four weeks to an internal rough cut. One week or two weeks to broadcaster rough cut, which is a very lax schedule and it’s really awesome, but basically we have almost zero notes. We have no fine cut, and we have no lock. So it all works out in the end.

Jonathan Dowler:

She’s downplayed it, but I have to say these are some facts that Jen was actually able to give me. To give you an idea of the shoot and the quantity of footage that two hour comes from, it’s 95 days of the shoot for the season over four months, and there’s eight hours per day times two cameras, so roughly 16 hours a day of footage. Then that equals about 96 hours of the main cameras for the season. GoPro gets roughly around three hours a day. Drone footage to capture the vistas and make it a little cinematic is four hours per episode. Yeah, so basically over 14 episodes, you could be looking up to 1800 hours of footage to deal with. And so the way you approach story and the way this workflow is supposed to work, you have to be really on your game.

Jenypher Fisher:

That’s not including, by the way, we have the footage from all four of the … We’re in season six. We have footage from all five of the other seasons. That’s all open game. If you need cover, you have to go look in post seasons, so that’s another 1800, and another 1800, and another 1800.

Jonathan Dowler:

All parts of the buffalo. I think that’s absolutely incredible.

Jonathan Dowler:

Ian, what would you say in terms of your average workflow on a show, like either Forever Young, which we’ll see a clip for later, or In the Making?

Ian Sit:

Those two actually differ quite a bit. I’ll talk about In the Making.

Ian Sit:

In the Making was very much a director-driven series, and so the producers had the mind to give the director as much flexibility as far as workflow, and they were far less streamlined. So it was usually a direct relationship between the director and the editor and one other assistant editor. There was one story producer that sometimes gave us notes and time codes, but a lot of the times, it was just a paper edit or a direct conversation with the director before we tackled the footage.

Ian Sit:

Similar, it was a half an hour show. We had four weeks to do an internal rough cut. I don’t think any of the episodes stuck to that schedule. It went way beyond because it was a lot more trial and error with this show that we, in fact, cut many versions of a lot of these episodes, which at the very end of it, because there was so many chefs in the kitchen, they couldn’t quite decide on what they wanted. We had to go back to ground zero. So it was not an easy show to do, but I think ultimately all that hard work showed up on screen, and I’m proud of that.

Ian Sit:

With Forever Young, which is a one hour doc, for that one, it was a lot more of a “Here you go. Here is a bunch of footage. Try out whatever you can, and then I’m going to continue shooting …” This is the director speaking to me. “And then we’ll come back, and then we’ll see what you’ve done, and then keep shaping it from there.” It was a very, very organic process. So that’s basically how you get into it. It wasn’t really structured is what I’m trying to say, but because the director is so competent and efficient with the way he works, he knows exactly what he wanted, which is such an asset when you’re working with someone, that it turned out to be quite an easy, not a very stressful edit.

Jonathan Dowler:

Basically, it starts of, I guess, from production. You’re getting the idea from production or producers saying, “This is the rough idea of what we’re going to go for,” and then you get a string-out, be it handed down from the director or from the story editor. They’ll hand it off to you, and that’s your starting point. But you both seem to be left alone to experiment and find the story.

Jenypher Fisher:

I call the string-out an opening theory. That’s exactly what it is. Some theories are better than others. Some are not a good thing at all. What you’re given to begin with is probably not what you will end up with, anywhere close to it. It’s just here’s an opening thought, then we all as a team tackle it.

Jonathan Dowler:

Tackle it. Well, then let’s go over to reality competition, because at least in terms of reality competition shows can be built around competition. Baun, if you can just give me an outline, how is the story process streamlined in a competition show like Amazing Race or Top Chef in terms of how is the story handed off to the editors, and then your process there?

Baun Mah:

On the bigger shows, you end up working in teams. I don’t think I’ve ever done a large challenge show solo.

Baun Mah:

So what you do is you start off with usually there is a lead editor and then a team of editors with them, probably usually just two or three other editors. You get together with the story editor, who helps you facilitate all the story and what they feel like is the through line through the episode.

Jonathan Dowler:

So it’s like a meeting? Like they have a —

Baun Mah:

Yeah, yeah, it’s a meeting that you have, and depending on who you’re working with, sometimes what you get is a paper edit. Sometimes they actually have selects for you ready in Avid. The really good ones have somewhat of an assembly or at least markers so that it saves you time from sifting through all the footage, and you can just look through the markers bin. So it almost reads like an annotated notes kind of deal.

Baun Mah:

And then we split up the work between all the editors. For example, it’s different for every show, but for example, Amazing Race … For assembly, we have 13 days, so on day one is when we have this big story meeting, and we divvy up the work. Day five, we have an A-line screen, which is like our radio edit. So what we try to do in those first five days is go through all the footage that’s relevant to our sections. We go through all the sound bites to see what is relevant, and we try to make our story beat. So typically a story beat would be you try to land it somewhere between 20 and 30 seconds. Sometimes, if it’s a really good beat, it goes a little longer. But anything more than that, especially on a show that’s as fast paced as Amazing Race, it actually feels like it drags in the end.

Baun Mah:

So you try to break up your story beats that way, and then on day five, you screen it together, just so everyone gets a sense of where the story is, where the characters are, whether or not a beat is working. And there could be multiple beats that have … For example, a team could be struggling. It’s like where is the best example to show where this team is struggling? So that’s where you figure that all out.

Baun Mah:

And then you have another four or five days, so day nine or 10, you have the internal screening with the whole team, the story editor, and our post producer, where we then get notes from the post producer. And then on day 13, we screen with the showrunner, and then we get his notes.

Baun Mah:

And then we go into what’s called the screen cut. So we have four days to do the screening cut, which is then shown to the executive producers. We get notes from them, and then we finally get to the rough cut, which is five days, and that’s just with the lead editor. The other editors go on to do other episodes. You have five days to clean all of that up, and really a lot of the challenge comes from bringing it down to time, because some of the rough cuts can end up being, for a 44 minute show, the longer ones … I haven’t worked on a premiere, but I know the premieres, I have heard, have ended up being like an hour-10, and hour-15. I remember in Season Four, our Vietnam episode was an hour-25, so we really had to cut it down.

Jonathan Dowler:

In terms of races, to give you an idea, some people question … One of the questions, I don’t know if we’ve got some of them, is why are so many editors needed to tackle this, and it could be broken down quite simply by schedule, which you’ve just heard. But an example for Race, on our first episode or season premiere of Race, so it could be a longer episode or it comes down to right time, on average, 101 XD cam discs, which is seven per team, including interviews. So, yeah, you basically do 101 XD cams. Each one of those, about 70 minutes. You’d have 42 GoPro cards for various helmet setups. You would have car cams, and then you’d have a drive full of drone footage. And then 56 audio cards, which is almost every contestant is mic-ed. You have the on-camera stuff.

Jonathan Dowler:

And then I should say on the XD cam is also the mats, the various zone cameras, so if you are ever wondering why a certain number of names are on anything, it takes a lot of teamwork and a lot of effort to get to those schedules.

Jonathan Dowler:

And did you want to say, in terms of a rough cut, are you talking about some music, maybe some black gaps, or are we talking about-

Baun Mah:

No. Yeah, and this is more of a trend that I feel personally is not great that’s happening is we no longer have what is known as a traditional rough cut. Our rough cuts include sound effects, music, lower thirds, graphics …

Elianna Borsa:

It’s polished.

Baun Mah:

Yeah. It’s polished. It’s a polished cut.

Jenypher Fisher:

Color correct sometimes.

Baun Mah:

Yeah. Sometimes because you know you’re going to get feedback saying “This shot is too dark,” so if you have the time, you try to color correct a little bit. So that’s what our rough cut is. It’s basically a finished cut. Other than the length, it’s air-able. So it takes a lot for the rough cut, and especially with a show like Race, which is super, super fast-paced, if you look to the timeline, if you look at any Timeline Tuesday, if you look at the whole timeline of the episode, it’s basically all black because of all the cuts. You can’t even see where a cut begins and where it ends. And, yeah, we end up doing 16 to 18 tracks, and you have four or six of those are dedicated to sound effects. Once you watch a couple clips we have, you’ll see that there are a lot of sound effects.

Baun Mah:

And each music beat really only lasts as long as the beat itself, so it’s wall to wall music, but it’s 20 seconds of music, and then you have to find the next track. And one that fits the mood and the moment.

Baun Mah:

So, yeah, it is a lot of work to get to that rough cut. Yeah. So just to pick up, so then you get the rough cut, you get the network notes. It’s two more cuts for the fine cut, and then you have one day to picture lock. And then it’s like beginning of that day and then end of day that should be done.

Jonathan Dowler:

And that goes on all summer long.

Baun Mah:

How many days is that total? I didn’t even calculate that.

Ian Sit:

Sorry.

Baun Mah:

It’s your typical 25. I guess … Yeah, that’s around typical. 25, but it’s like the show is on steroids, so you feel like you could always use more time.

Jonathan Dowler:

And then just to give an idea, Elianna, one of your first gigs you were working on was Big Brother. Just give an idea, what would you say just in ballpark … Big Brother has about 64 cameras running 24/7, 50 microphones, and turnaround, Elianna? Can you just give us a rough thing on how you remember Big Brother, just a ballpark?

Elianna Borsa:

Well, Big Brother, obviously as you know, it’s like three days a week the show airs. So, for example, when we’re doing challenges, they will film the challenge, one of them, on a Thursday night, and by Sunday it’s on TV. So you have a very short amount of time, and it’s obviously a ton of footage. Sometimes the challenges can go up to three, four hours, really depending on if it’s endurance.

Elianna Borsa:

And then it’s really cutting it down, figuring out who we really need to concentrate on. For that kind of show, it’s like who is going to be nominated, and who the Head of Household is.

Jonathan Dowler:

The end of the story, where you’re heading to and stuff.

Elianna Borsa:

Yeah, and then cutting that all down.

Jonathan Dowler:

But, again, it’s teamwork stuff as well. It’s like you’re left alone in as much as your section of Race or Brother, but then you also have to work as a team, which is a different —

Elianna Borsa:

Right. It’s all very collaborative, and there’s a ton of editors. And mostly if you’re not working on challenges, you are taking scenes, and then sometimes you’ll work on a scene, and it doesn’t make it into the episode because something else just happened right now. And that’s more important than maybe a comedy scene. You can’t be precious about your scenes for sure. But, yeah, it’s like Big Brother is very collaborative and super fast paced.

Jonathan Dowler:

Why don’t we dive right into a scene, seeing as we just talked a bit about Race, because that seems to be digestible. And then we’re going to talk about some factual stuff. So, Baun, do you want to set up the scene that you have from Amazing Race, and the challenges? You’ve talked about some of them already, but just set up the scene from Amazing Race.

Baun Mah:

Yeah. So I chose a really seemingly simple scene, and in the larger scheme of the episode, it is a simpler scene. I don’t want to give too much because hopefully you guys get the story because that’s the whole point of the panel.

Baun Mah:

So, basically, so these teams, they’re coming from Indonesia. They’re landing in Toronto. They have to get to their next location for their next challenge.

[Clip Plays]

Speaker 8:

Go, go, go. Hold hands. Hold hands.

Speaker 9:

There they are. We’re free, [inaudible 00:23:10], we’re free. We’re at info.

Speaker 8:

Board the Chevrolet Equinox to where it was assembled in Canada.

Speaker 10:

The Chevrolet Equinox has been assembled at the CAMI assembly plant in Ingersoll, Ontario, since 2004. Teams must now determine the location of CAMI Assembly, and drive themselves to the two million square foot facility, being careful not to confuse this plant with any other Chevrolet plants in southern Ontario.

Speaker 11:

How about these guys?

Speaker 12:

Hey, question for you.

Speaker 11:

We’re looking for the Chevrolet Equinox assembly line center.

Speaker 13:

Located at 300 Ingersoll Street.

Speaker 12:

Write that down. Ingersoll, Ontario.

Speaker 14:

Ingersoll.

Speaker 11:

And that’s CAMI Automotive?

Speaker 14:

Yeah. C-A-M-I.

Speaker 11:

Okay.

Speaker 12:

Let’s go. Let’s go.

Speaker 11:

Let’s rock and roll.

Speaker 12:

Yeah, Chevrolet Equinox is made in Ingersoll. Some of them are made in Oshawa. The Equinox is made in Ingersoll.

Speaker 11:

Okay.

Speaker 12:

I would not be surprised just how many end up in Oshawa.

Speaker 15:

We are headed to Oshawa to the GM plant. Head east towards Oshawa.

Speaker 16:

We just stopped for directions, and now we’re just heading out all the way to Oshawa.

Speaker 15:

Oshawa.

Speaker 16:

GM Oshawa Assembly.

Speaker 15:

Oh, another car is here. Oh, my God, two other cars are here. I am very confused as to where we are supposed to go. It says to where it was assembled in Canada, so maybe this isn’t where it was even assembled. Hmm. What are we thinking? I have a feeling this isn’t it.

Speaker 16:

I think you’re correct.

Speaker 15:

Do you guys have a phone we could borrow? Ingersoll. Ingersoll.

Speaker 16:

Ingersoll is another hour and 45 minutes past Toronto on the other side.

Speaker 15:

Oh. We have headed east. We now need to head west.

Speaker 16:

Ingersoll. Coming up, baby.

[end of Clip]

Baun Mah:

Okay, so I mean that is a relatively simple scene. It’s two minutes. I trimmed out the part where the teams that knew where they were going went to the right location, so that was maybe another 45 seconds. So altogether, this moment lasted two minutes and 45 seconds in the final cut. There were actually 30 hours of footage just for this. Because the teams did get lost, the camera is on all the time in the car, you’re looking for sound bites. Because as we were doing the radio edit, you’re looking for any relevant sound bites, any interesting sound bites, any interesting moments. So I hope it seems very clear here, but really it was like a huge mess from when they landed in the sense that everyone went looking for someone with a cell phone.

Baun Mah:

There were conversations that were really interesting because some of them did debate. They were like, “Where is it built? Oh, there are all these locations,” and usually you’d be like, oh, that’s really interesting because they’re trying to figure it out. Some people would go to gas stations, so we showed one of the gas stations, but really the teams that got lost and even some of the teams that went to the right location, they would stop off at gas stations, have conversations there.

Baun Mah:

The rough cut, when we showed the assembly cut, this was an 11 minute scene because the teams, when they arrived in Oshawa, they actually explored the plant and no one was there, and it was like actually really fun because they were like, “I feel like we’re going to get arrested. This doesn’t feel right.” It’s all good stuff, so we kept it in. And then with the cheerleaders, Leanne and Mar, in the previous two episodes, they were actually number one. They won both legs. So we cut out this whole section because they went to Oshawa. They ended up at a whole different part of the plant, and then things started getting tense, so they started getting a little more agitated with each other, and you could see that they weren’t really working as a cohesive unit. So there was conflict there, and it was interesting conflict because they were getting frustrated that they couldn’t find the location.

Baun Mah:

All of that very interesting, all of that that we had, but then it was too long. Once we did our radio edit and also I think we even went up to the internal screening with a post producer. There were more interesting moments, like at the very end of this episode the teams also got lost in Stratford not being able to find the final mat. And that was more interesting. That ended up being more interesting than these moments, so we had to come back to these, and revisit, and see what we could cut down.

Baun Mah:

So what we did anchor it on were what we considered two pivotal moments was when the teams who got it right … You heard the woman say there were two GM plants, one was in Oshawa, one was in Ingersoll. I can see how people could get lost going to Oshawa. And that was the key moment there. We decided, okay, we’re going to sum up this whole little moment in this one sound bite. That’s what sort of helped us clean up the rest of it because we just wanted that to be the message of this whole little travel beat.

Baun Mah:

And then the next moment is when they all end up at Timmy’s, but what happened is … So three of the teams did end up at Timmy’s, and they crowded around each other, and everything happened like it happened. But the cheerleaders actually didn’t go there. They went there, they saw that there was a crowd, and then they left again. And then we did have this whole moment where they went back to the plant, they talked to a security guard there, and the security guard actually told them that there’s another plant in Ingersoll, and that’s where it sparked.

Baun Mah:

But because the security guard and … People ask us sometimes why we cheat things in reality TV. In this case, it was very practical with the security guard. The security guard didn’t want to be on camera, so we didn’t have any vis of the moment, just audio. We didn’t have time to put those girls back at the Oshawa plant, so what we did was we just took the little bit of them entering the Timmy’s and exiting, and then just formed that moment. Made it just one big moment, and then that was the pivotal moment for the teams that lost realizing where they had to go.

Baun Mah:

And then so it ended up being from 11 minutes to 2:45.

Jonathan Dowler:

But you can also argue that essentially, talking about truth and fact is basically they figured out their mistake, and that is the truth-

Baun Mah:

Exactly, yeah. Yeah.

Jonathan Dowler:

But it’s just collapsing it so you can make it-

Baun Mah:

Really, really condensing it just so that we had distilled it down to the basics. And, like we said, Leanne and Mar had all this tension building up as a team, but later on in another challenge, there was also a greater moment of tension. So working with the story editor, I actually was really fortunate because my story editor was Seth Poulin, who was actually a lead editor on the show for three years, so he knows how this show goes. So we talked about it, and he was actually really great in helping whittle it all down. And his whole motto was you may have 10 great moments, but what’s the gold? So you have 10 great moments, but can it be distilled down to five great moments, and still keep everything that you want? And that’s the mentality that we go in with.

Jonathan Dowler:

And you say that the prime rule on Race, if you had to order the priorities when you approach a scene, would be clarity first?

Baun Mah:

It would be clarity first, so that’s why you string it out. And then it’d be trying to maintain that clarity while cutting it down to like one-fifth of what you had.

Elianna Borsa:

Yeah. As you say with that clip of that one girl in the car saying, “Well, I’m sure a lot of people will mess this up, and go to the wrong place,” it’s really making sure that every word, because it has to be cut down so much, that every word matters unless it’s comedy. So if something is in there that doesn’t matter, it’s not helping the story, then we don’t have time for it. And if you’re not listening when you’re watching that show, you might have to rewind because you’ve definitely missed something.

Baun Mah:

Totally.

Jonathan Dowler:

And would you say, in terms of you finding that, is that you going through the 30-odd hour so footage?

Baun Mah:

For the travel beats, usually, because there’s so much to do that the story editors that are helping us, they tend to focus on the challenges and the mats. Travel beats are usually left up to the editors. Sometimes, like when the story editor has time, they loop back around and help you clarify things. So Seth did loop back around. We talked about it. He went through some of the raw footage as well. But I feel like that’s a luxury. Usually it is up to the editor to condense these travel beats, and find what’s interesting in them.

Jenypher Fisher:

I have a question. When you do this, when you’re looking for something and you know you’re looking for something, how do you find it? Do you use the waveform to figure out where people speak?

Baun Mah:

Yes. That’s all we do.

Jenypher Fisher:

Or do you listen to things and fast-forward, or a combination of the two?

Baun Mah:

There’s a mix of both.

Jenypher Fisher:

These are great tips.

Baun Mah:

Yeah. Depending on your system. If your system can handle fast-forwarding, because we’re doing multi-cam, too, especially in challenges. But, yeah, on these travel beats, you could definitely … Because it’s a single camera on each team. So you can scrub through at one-and-a-half or two times speed. I usually look at the waveforms, so as soon as I see someone talking-

Jenypher Fisher:

Listen to that.

Baun Mah:

Yeah, I listen to that. And that’s why we do the radio edit because we barely pay attention to visuals. Like maybe you can make a mental note, or put a marker when you see something interesting, but usually when you’re doing your A-line edit, the radio edit, you’re literally just looking at waveforms, and sound bites, and trying to form your beat using that.

Elianna Borsa:

Yeah. And sometimes it might not exist in that travel beat, and like you said, there’s previous episodes and their footage, and you might just go in and grab them saying “There it is” from another episode.

Baun Mah:

Yeah, 100%. Even when Courtney was summing up the whole thing about how you go to Ingersoll or Oshawa, the camera wasn’t on her the whole time, so you saw that I cut away to her brother, and that shot was from way later in the footage just because the camera didn’t stay on her at that time.

Jonathan Dowler:

Well, I think we’re talking about using all parts, all things that you can find to tell the story appropriately. I think that throws really well to, I think, Jennifer’s scene, because I think, Jennifer, on a factual show like Jade Fever, you’ve got a different sort of challenge. You’ve got the shooting over the course of the season, so how do you approach a scene and build it out? Because there’s not so much a challenge to build around, so what is it built around?

Jenypher Fisher:

It’s always built around character. Character, character, character. Always character.

Jenypher Fisher:

My process, it’s always the same no matter what I’m working on. I could be working on a two hour doc doing a nature of things. Honestly, I’ve done Bachelor. I did the same thing on Bachelor. I’m specialized in men’s TV. I don’t know how that happened, but it did. My process is almost always the same. I have a super bad memory. I generally go to the writer and say, “Tell me the bullet points. Don’t go into detail. I won’t remember anything you tell me that happens in the back of the show. Just give me the least amount of information humanly possible.” Then I’ll watch the string-out. I will forget. This is a four act structure. I will forget acts two, three, and four. It’s not going to stay. But I will actually watch it.

Jenypher Fisher:

Then I actually am super linear about the whole thing. The way I do it is I watch the string-out for the scene that I’m currently working on. I fix the audio, because honestly, I could get audio that’s parsed down because someone actually knows how to use Avid, or I could get 16 tracks of I don’t know what this is. I have to find the mics of the people who are in the scene, not the ganged mics. The actual mics. They could be hidden because often I’m dealing with track two may actually have four mics on it, so I’m having to search through all that, find the mics.

Jenypher Fisher:

While I’m actually sorting the audio, because I’m kind of militant about audio, interview on one and two, background on … I’m super organized about it because if you’re not organized at the front, the back end is just going to be a mess. I’m also familiarizing myself with the footage. It doesn’t take that long, but you’re actually really getting the story. You’re starting to drink it in, and you get to understand while you’re doing that what the problems with the scene are.

Jenypher Fisher:

Then I always go talk to the writer. Even though I have 10 days all by myself, it doesn’t mean I don’t get up, walk to the writer, sit in front of them. It’s not something I do online. I need to see their eyes. I need to understand, and I say, “What is the story you are trying to tell?” Whether or not they actually told it, I want to know what they want to tell because that’s what I have to make.

Jenypher Fisher:

And then I literally just go for it, then very linearly start putting it together, keeping in mind most importantly who the show is for … Most importantly … The broadcaster and the audience. You always cut for those two things. I’m not making a soft documentary most of the time. I’m making men’s television, and I need to know that it’s for men between the ages of 16 to 34, and the broadcaster is History, and they want this. And that’s what I need to deliver. Because I only have 10 days.

Jonathan Dowler:

And so when you’re given a scene, why don’t we talk about the Jade Fever seen now? This is a series that is still ongoing. This is an earlier cut that you’re dealing with right now?

Jenypher Fisher:

This is actually a cut I’m currently working on. Actually, we just locked it on Thursday. So this is locked. Yay.

Jenypher Fisher:

So this cut is from a show I work on called Jade Fever. It’s in a place called Jade City up in BC. They mine for jade, which is technically giant pieces of rock. They don’t look like anything until you actually saw them in half. Then you see the green.

Jenypher Fisher:

The wonderful thing about this clip, and I’m going to set the clip up slightly, is … And a friend of mine said this the other day. Reality never works the way you want it to on TV, which is exactly what we’ve been talking about.

Jonathan Dowler:

It’s just the whole thing. Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

And this sequence is completely true and about 80% made up. Like I didn’t have so much stuff. I’m going to tell you the problems I had, then we’re going to watch.

Jenypher Fisher:

This is the end of a six year journey for them to sell jade. We’re in Season 6. They’ve never sold jade on their own. Never. Not once. This is the pinnacle, this is the moment. I had nothing. The buyer, it’s a Vietnamese buyer, he’s the only Vietnamese guy in there. You’ll know him. He showed up to buy a rock. It was still being cut, so technically it just looks like a rock. You can’t see green. There’s no green. It’s not cut. He agrees to buy it, and he does buy it two days later when they finish cutting it, and they’ve actually taken pictures of the jade and sent it to him in Vietnam because he’s leaving. He’s not going to be here tomorrow.

Jenypher Fisher:

This is a problem because it’s a show about jade. You want to see the jade. I watched the scene, and I’m like, “You can’t see the jade. This is a terrible thing. When is the jade cut?” “The next day.” “Is he there?” “No.” Okay. I’m going to try and marry these two days. That’s the problem because the buyer is gone, he’s left, he’s gone. It’s sunny the day he’s there. It’s raining, it’s cloudy, but that’s fine. I’ve done that before. We can figure this out. I don’t have a picture of the jade falling to the ground because no one was shooting that, unfortunately. Usually, we’re pretty good at that, but they didn’t get it, and there are only two people present. There are, I think, six to seven people. The day he bought the jade, there’s only two people.

Jenypher Fisher:

So at the front of the scene, you’ll notice there’s only two people, and it’s sunny. And as soon as the Vietnamese buyer goes up, the weather changes, but no one really notices. And then he buys.

Jenypher Fisher:

There’s many, many more problems. I’ll tell you about it after the clip.

[Clip Plays]

Speaker 17:

Going to be close.

Narrator:

Early evening at Two Mile …

Speaker 17:

It’s going to fall over.

Narrator:

The clock is ticking.

Speaker 17:

You start hearing it cut hard like that, it’s getting close.

Narrator:

The crew have just one more hour to try and sell a jade slab to their buyer, Mr. Long.

Speaker 19:

I don’t know. We’ll see what happens.

Speaker 17:

There. Now it’s done. It’s a big chunk of jade.

Speaker 19:

Beautiful grade.

Speaker 17:

Now, before he flies out, he can see it. I hope it’s good.

Narrator:

If Mr. Long likes what he sees, this sale could go a long way towards paying for their mining season.

Claudia:

This is it. Our last visit.

Speaker 19:

Yeah.

Claudia:

Ooh. We’ve worked so hard to get here. This could change everything.

Claudia:

Okay. Is that good?

Narrator:

Mr. Long has to make sure he can work around any fractures to carve this piece of jade into a five foot tall Buddha statue.

Claudia:

So, Long, are you still thinking about it?

Mr. Long:

[inaudible 00:39:04] is good.

Claudia:

Yeah? This one’s a deal? Like a handshake deal? Like a yes?

Mr. Long:

Yes.

Claudia:

100%? 100%? Okay. I think I just sold jade.

Josh:

That’s happy dance right there.

Speaker 19:

That’s the best.

Claudia:

This is what we mine for. This is our dream.

Speaker 19:

We got a job next year maybe. We got a job next year maybe.

Narrator:

Claudia has just landed a $250,000 jade sale.

Speaker 19:

Thank you, Long. Thank you, buddy.

Claudia:

This is exactly the moment that we’ve been waiting for. Took 10 years.

[end of Clip]

Jenypher Fisher:

So that’s an unfinished scene. That’s actually my voice. Yay. I love doing voice over. I used to suck at voice over. The first time I did a rough cut, the guy behind me, the executive, went, “Can’t you even try?” And I sat in my seat like this, going, “Oh, God, it’s an hour long show and this is Act One. We’re in trouble.” And so I endeavored to get at least better.

Jenypher Fisher:

So other problems I had. There’s only two people. There’s two guys in the sunny scene. I inserted the third guy, who is the younger kid who does the happy dance at the end. He’s the guy I love. He’s good at TV. He knows he should do stuff like that, and I will put it on TV. We call him a clip monster. He’s always one you look at. “What did Josh do? What did Josh say? He probably said something useful.”

Jenypher Fisher:

I inserted him into the footage from the 29th into the footage on the 30th, to actually try to marry the scene so that you would think Josh was there, and it wouldn’t be weird that he suddenly popped up with Mr. Long. Because he didn’t arrive on an ATV. Only the two of them arrived.

Jenypher Fisher:

There’s an actual wardrobe change that I don’t think anyone noticed. One guy goes from wearing a bright yellow thing to a dark thing, but it doesn’t matter because there’s a couple shots in the middle, and there’s time for him to have taken off his jacket.

Jenypher Fisher:

I couldn’t show the buyer, Mr. Long, with the jade because the jade was still being cut. It just looked like a rock, and he’s buying a finished thing. That’s a problem, so every cut away of jade is not the jade. It’s from some day at some point of some rock. While I’m picking jade, it has to be plausibly the rock he has bought. It can’t just be any rock. It has to be believable. So it kind of cuts down.

Jenypher Fisher:

The buyer, Mr. Long there, was not super clear about buying the jade. He kind of took a minute to go, “Eh, eh, eh.” It was not rewarding at all. The piece of jade you see him buying there isn’t the jade piece I want you to think he’s buying. It’s a second piece of jade he bought later in the day. That one was way more rewarding, so I faked it. So it’s completely true he bought the piece of jade. He bought a second piece of jade much clearer, so I took the footage from the second piece of jade, and made him buy the first piece of jade using that. Which was a problem because directly behind him is the piece of jade I want you to think he’s buying, and directly in front of him is the piece of jade I don’t want you to think about. So it’s a problem.

Jenypher Fisher:

And the entire thing is pretty much … Oh, and actually Claudia, they were pretty much all business. They did not smile a lot. So every smile you see in there is every smile I have. Like, all of them. It’s all wrapped around Josh doing the happy dance, which I was so happy to see. Because I’m like, oh, someone’s excited, and Josh wants to high-five people. It’s like, sweet, I’m going to split that into two, and I’m going to sparse it out just to make it seem happy.

Jenypher Fisher:

And every closeup you saw in that whole thing, both before and after the tension and the happy, was taken around a back of a pickup later in the day when they were discussing lunch. Because no one got closeups. But I needed to create tension, and then I needed to create happy. So you just do what you have to do. It took awhile, but completely true … Not at all true.

Jonathan Dowler:

My head is almost spinning out because you’re like “I don’t have this.” “Oh, yeah, the one thing you need? Yeah, we didn’t get that.” And then I guess there’s varying degrees of that because some camera will get all the shots. You got that perfect shot of the slab falling off, but then-

Jenypher Fisher:

After it fell.

Jonathan Dowler:

After it fell.

Jenypher Fisher:

Which is fine. I have to say, as an editor, for the first 10 years, I was super like, “Why didn’t the shooter get that?” And then I really sat down and started to think about what these guys are doing, and what these girls and guys are living with, and the cacophony of chaos that’s in front of them all the time. And I’m less harsh on them now because I’m like, I don’t want to go out there. I want to sit in my chair.

Jonathan Dowler:

A senior editor I once knew said, “I really want to become a cameraman because I think that it would be one of two things. If I go out to try and shoot something, it’ll be either easier than I’ve ever thought possible, and then I have a new job that I can do, or it’ll be the hardest thing ever in the world, and I’ll shut my mouth, and I’ll happily go back to editing.”

Jenypher Fisher:

It’s that one. It’s that one.

Jonathan Dowler:

And so, yeah, he never got to try it, but I think that was something that’s resounded with me.

Jonathan Dowler:

So were you pitched this scene of this is the scene, this is the big thing. You’ve got to make it work.

Jenypher Fisher:

Yeah.

Jonathan Dowler:

Or did you realize this is it?

Jenypher Fisher:

Pretty much.

Jenypher Fisher:

No, it wasn’t pitched to me as this is the scene. I just watched it and knew what that was, and then I went to the writer and went, “We can’t have a rock that you can’t see. How do we fix this?” I think I said, “When does the jade fall? Can we use that?” And they’re like, “Well, it’s supposed to be in the next episode.” I’m like, “It can’t be in the next episode. We need it. Go get it.”

Jonathan Dowler:

And then they’re like, well, that’s going to cause a problem in the next episode. You’re like, “I’m not editing that episode, so-“

Jenypher Fisher:

Yeah, I don’t care about that episode, nor am I finishing that episode, so I could give a rat’s ass.

Jenypher Fisher:

No, this was all pretty much me going “There’s a problem.” I’m pretty experienced. I’ve been doing this. It’s not my first rodeo. Me going, “No, there’s a problem. I think I know how to fix it. Just let me fix it,” and then doing a rough string-out, showing it to people and going, “Eh?” And then them going, “Keep going,” and that’s how. It’s just all initiative. It’s feel. It’s instinct. It’s what you know. You know what you have to do.

Ian Sit:

This thing that Jennifer’s talking about, not having enough footage to create a scene, I find that we’re often confronted with this. And it’s a strange paradox where it seems like you have hundreds and hundreds of hours of footage that you have to sort through, and yet not have the shot that you need to create a two minute scene.

Baun Mah:

Yeah, you’re always missing that key moment.

Ian Sit:

And so what I find that is strange but perhaps should happen a lot more often is just having a conversation or being able to talk to your DPs prior to … I don’t know how often you guys get a chance to talk to production, but telling them in order for us to get a scene, if you’re going to shoot a jade thing, please shoot it. Have a closeup. Or hold your shots for more than 10 seconds please so that I can cut to it, and–

Baun Mah:

I’d like five. Five seconds, please.

Baun Mah:

I’ve thought that way a lot, too.

Ian Sit:

Yeah.

Baun Mah:

And now, seeing what production goes through, I will say that, especially on these competition shows, they don’t know what the through line is. They’re just trying to get everything they feel is relevant. I would love them to hang on a shot a little longer.

Baun Mah:

Let’s say, for example, the Food Network show. We have 10 chefs, and only three cameras, and they have to capture everything. And, you’re right, we often miss those key moments that we need that end up being in the story, but at the same time, I can’t imagine how they could predict some of it. The jade seems like maybe they could predict that a little more.

Elianna Borsa:

Yeah, maybe.

Jenypher Fisher:

It’s going to fall.

Elianna Borsa:

I should say what’s great about this scene is, as we watch it, it doesn’t seem like it was something hard to cut, because it just seemed like it was there, right?

Jenypher Fisher:

Yeah. It’s right there.

Elianna Borsa:

So that’s the thing about reality TV oftentimes, especially on the Race, is I was told when something looks like it might have been easy to edit, you’ve just done a really good job of doing exactly what Jenypher did.

Jenypher Fisher:

I will say one of the things I do, and I probably get away with it because I’m older and people know me and they trust me … I’m not sure I would do this with someone that I was just starting to work with if they didn’t know me … Is I refuse to put music in till we’ve nailed the story. It’s a privilege I have because I know my boss, and I know my boss trusts me, but I absolutely will not music in. I’ll put sound effects in. I will absolutely smooth the audio. It’s going to sound great, but there will be no music. I can hear all the music in my head. I actually build for the music. I know the moments. All the pensive stuff, that was there before. I just refuse to put it in until we’ve nailed the story enough that I’m not going to have to re-edit the music over and over again.

Elianna Borsa:

You are very lucky.

Jenypher Fisher:

And that’s a privilege. I know.

Elianna Borsa:

That’s nice.

Jenypher Fisher:

I know. But it works really, really well because once you put the music in, you can mask a lot of stuff. You can fool a lot of people for a really long time, but then someone is going to go “This doesn’t make any sense, but it’s flashy.” And that’s when you’re really in trouble.

Jonathan Dowler:

Ian, how do you approach music then? Do you bring stuff into your clips? Do you bring the music in, or is it-

Ian Sit:

I have the exact same attitude as Jennifer. I try not to add music until I know the story is functioning, until you hit your A-B-Cs, I will not put music in. And then, strangely, we’re editors, so we’re very visual, but, honestly, you always work with the audio in terms of getting your pacing right. And sometimes I’m closing my eyes when I’m editing, which sounds strange, but you do it, too, right?

Jenypher Fisher:

I absolutely do it.

Ian Sit:

Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

I spend half the time with my eyes closed.

Ian Sit:

You close your eyes. You kind of find your selects. You put it all together, and then you just want to hear the rhythm of the speaking just to know that you have what you want in terms of how you want the scene paced out. And then you look at the visuals, and that’s when you realize you don’t have what you want, and you’re swearing all the time. You’re like, “Oh, damn it. Hold the shot a little bit longer.”

Ian Sit:

And then at the end, that’s when you put the music in, and you make your adjustments. So the pacing of the audio that you’ve constructed in terms of how you want the scene to play is what informs the music. You can use a music track to inform your editing, but I find that that tricks you into building moments that don’t actually exist in the footage that you have. So I try to reserve that process of adding the music until as long as I can before producers and director-

Jonathan Dowler:

Let’s just talk about building your storyline, the audio. When you close your eyes and you’re listening to stuff. When you’re talking, a lot of this is written by the interviews, by the on-the-fly, off-the-cuff interviews both in the situ and after the fact, like in the interview stuff. For example, in the Jade Fever scene, just at the end, she’s like, “This is the big deal. We’ve done this whole time.” Let’s talk about, because this is a frequent question for unscripted, you’re writing it through their interviews. Do you fake what they say or do you make them sound better? What would be your approach? We call it franken-editing. Franken-grabbing is a term.

Jenypher Fisher:

I hate that word.

Jonathan Dowler:

Yes. It is thrown about quite a bit, but a lot of people say, “Well, I didn’t quite say that,” but you’re writing it using their words. Let’s just talk about how you build up your A-line stuff.

Ian Sit:

You do it in terms of being ethical about it. I think you do exactly what Jennifer did with her scene, whereas like it all happened. This is what actually happened, but you don’t have the footage or the person saying exactly what they are trying to say, and so you cut it, and you do manipulate the arrangement of the words occasionally in order for them to actually say exactly what they wanted to say.

Jonathan Dowler:

Or to be more clear. In an example of Race, to be absolutely clear.

Ian Sit:

Exactly. You’re cutting out um’s and uh’s and pauses, but sometimes people speak circularly … You know what I’m trying to say.

Jenypher Fisher:

Circularily?

Jonathan Dowler:

If this were an interview, we would cut this part out.

Ian Sit:

I would be, yeah, cutting myself in such a way that would be far more coherent, and precisely what I’m trying to say.

Jonathan Dowler:

But exactly.

Ian Sit:

But you never, at least in my experience, I have a problem with creating a version of that person that did not exist in order for your to aid a story along.

Jonathan Dowler:

There are certain levels. Clarity and what happened, and speaking to that stuff, is what generally happened, or in the case of the Race would be like this happened, they got to this point, and how they got there, it’s too complicated to get into specifics about security guard, clearance, whatever, but you get to that point. And that is something like A-to-B that’s what happened. So, like you say, 100% true, but 90% constructed.

Elianna Borsa:

Unless you work on the Bachelor.

Jenypher Fisher:

All bets are off on the Bachelor.

Elianna Borsa:

Most of it’s true, but …

Jenypher Fisher:

“Yes, she really does love him.” That would be a bad franken-edit.

Jonathan Dowler:

I think it’s worth talking about, because Bachelor is certainly the black sheep that kind of comes up quite frequently, and there’s also a lot of discussion both online or whenever you’re dealing with unscripted or reality TV is I think in some ways when it comes to scripted, you have someone like an actor saying, “Thank you for the editor who was curating my performance along with the director in close …” Someone like Lupita Nyong’o would say, “Thank you to Joe Walker for editing me in 12 Years a Slave, because that’s my performance. It’s not me personally.” But we have characters or personalities that are cast in these reality sections, and they’re quite certain people. Certain people will certainly come up and will be quick to blame the editors. In this age, a lot of them are media savvy. Quick to blame the editors, saying, “I didn’t say it that way,” or “You made me say …”

Jonathan Dowler:

What would you have as an answer to that in terms of … We could talk about it more, but more of it just in general when they say, “I never said that,” or “I never did this.” What has been your experience with that?

Jenypher Fisher:

I, personally, don’t make people say things they would never say, with the exception of the Bachelor, which took me awhile to wrap my ahead around once I landed there. It’s just wrong. I would never, ever do it. I will make them say what they would’ve said had we been able to ask them in the moment. The fact is I’m editing four months after you shot. I only have this footage. Would they have said it? Would they object to me making them sound better? Hopefully not, which doesn’t mean I’ll take out colloquialisms. If people talk in a certain way, I’m going to use that. I’m just going to make it as clear as humanly possible.

Jonathan Dowler:

For example, we’re boiling down the characters, the essence. We don’t have time sometimes to bring out all the little nuances of certain elements. So, for example, in a series that’s as fast-paced and run-and-gun as Race, a lot of things that happened over the past season was an example of characters who were the villains or the bad people and stuff. And I think it’s nothing that, at least in my experience, it’s nothing that’s been done. They do do that, but we’re boiling down the essence.

Jenypher Fisher:

We just make them more them.

Jonathan Dowler:

More them. Yes. Elianna, you worked on the last season of Race. What would you say about the villain characters or how that happened?

Elianna Borsa:

Right, yeah. A lot of people were upset about those villains because they weren’t Canadian, and everything that we showed, that’s how they were and they were very competitive. And one of the guys, it’s in his character to want to win, and I’m here for a competition to win, and I’m going to try to get into your head no matter what. Because that’s literally his job every day as a boxer. So he took that there, and he really does have a big heart. I actually really liked him. But when you watch the show, and Jennifer hated him-

Jenypher Fisher:

I hated him so badly.

Elianna Borsa:

And I totally understand why you would because you kind of just see that side of him. But then we also want to show their good side, so we try to show that as well. But when they’re just giving “No, we’re here to win,” that’s what we got. And it makes good TV.

Jonathan Dowler:

And it’s mostly the impression of them. Certainly some of those elements, that’s just them doing the race. And people can take a strong view of it. But, you’re right, we’re showing them doing stuff, but I think in this age, a lot of people are media savvy. Young people who are applying to a show like Big Brother, they were just born when the first Big Brother aired, so they’ve grown up in this age of … And they’re very cognizant of editing. And that is certainly a challenge for people because it gets very meta.

Jonathan Dowler:

I remember some people talking about, “Oh, I was edited that way.” And then it becomes this whole thing of impressions and stuff.

Baun Mah:

I think definitely they’re very aware of how the show is done. Especially Big Brother, because there’s a livestream on both the US and Canadian versions, so they see everything play out in real time, and then they see the edited show. They’re like, “Well, that’s now how it happened.” Of course that’s not how it happened. It happened over the span of an hour and a half, but we condensed it into a three minute scene. And by doing that, by virtue of compressing, you’re creating a heightened version of whatever confrontation that was, or what that moment was.

Baun Mah:

But, yeah, the contestants especially are very aware of the cameras and what they’re saying. We even had a problem in Season 3 where the house guests wouldn’t confess to use in the Diary Room, because that’s where they’re supposed to tell their true motivations, but they were just so wary of trying to project their image that it took a lot to just say, listen, this is the one place where it’s a safe area, and we need to know what you’re really thinking in these moments. But they were just so in their heads about their image that it was actually really difficult-

Jonathan Dowler:

Overthinking it.

Baun Mah:

They were all super fans and strategists, so they just didn’t want to give anything up. They wanted to stay in the game the whole time.

Elianna Borsa:

Or an ego thing when they do really poorly in a competition, and they’re like, “Oh, no, but I wanted to lose then.” And it’s like but you went in there. We heard you saying that you really wanted to win. So on TV, they’re like, “No, I planned that.”

Ian Sit:

A lot of the time you’re actually making your subject look way better than they are. You’re making them look way more competent, way more interesting, way more coherent, and so the news you hear about Bachelor and stuff is like, “You made me look bad.” It’s like, what about 90% of the time we made you a lot better and more interesting?

Jonathan Dowler:

Very erudite and, yeah, you spoke really well and concisely, and so great. Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

Often, the longer a show goes, the more the characters get a little more … They know what you’re doing, and you end up asking them questions over and over and over and over again. You’re asking because you need them to say it in that space, and you need them to say it well. If someone asked me the same question for six years over and over again, I understand where they’re coming from, but we really just need you to say “I want to find jade.” Say it here, or whatever. I really just need you to say that. And it’s because you might have said it badly five times.

Jenypher Fisher:

Or confused. Like they think they said “I want to find jade,” but they didn’t. They talked about jade esoterically, and it’s like I don’t need that. I need you to say “I want to find jade bad. My family will die if I don’t find jade.” Or whatever.

Jonathan Dowler:

But I think also the great thing, just going back to your scene for a second, is the scene is very dramatic. You have to set up stakes through all that stuff, and you have to get those great … Drama is founded on the conflict and the stakes, and you set that up in your scene as “We need to sell this. Six years have led to this, this big moment,” and then you need that moment … It’s very dramatic. You are applying any sort of dramatic rules that we have in any sort of cutting, be it scripted or whatnot, but you’re kind of coming up with it without the right lighting, without the right shots-

Jenypher Fisher:

On the fly.

Jonathan Dowler:

On the fly.

Jenypher Fisher:

Yeah.

Jonathan Dowler:

Unscripted, and that’s to be commended.

Jenypher Fisher:

You still have to make a good story. It doesn’t matter what they shot. Best case scenario, it has to compete with the best scripted shows on television. That’s your competition. You still have to try to meet that, even though it was shot in two days in the middle of nowhere with one camera guy and maybe an audio guy. Your goals are still the same.

Jonathan Dowler:

That plays to the heart of it. A lot of the writing or the first draft could be in the planning of the shoot, so how often do you find, percentage-wise, are you given enough to work with when you cut your scene? When you’re given your scenes … Not to slam production. We’re not trying to start a fight with production, but in terms of are you getting enough story? How many times are you getting to the point of, oh, my God, we really have nothing. Like what you were talking about. So much footage and they didn’t get anything. Or do you find that more often than not you’re getting what you need?

Ian Sit:

It’s a process because it changes depending on the scope and the angle, the story that you’re approaching. So they might have gotten all the footage you needed. It just so happened that when you started editing, you took this direction, and if you’re going to tell this story in this scene, you have no footage. And so if you get into a point where you can’t go any further, and you’re stuck, perhaps you have it the wrong way, and then you go back.

Jonathan Dowler:

What you have versus what you planned for.

Ian Sit:

Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

Also, sometimes in the field they think they’re shooting one story, because they think that’s the story we’re going to tell, and in fact, that’s not the story we decide to tell four months later in post. We still have to use that footage that they were trying to tell that story to tell that story now. And that’s the job.

Jonathan Dowler:

I want to show Ian’s clip first. We’ll do the Ian clip, Forever Young. Ian, do you want to set this up for us, just talking about how you built this scene?

Ian Sit:

Yeah. This is from a one hour doc about immortality. It’s like a soft science show about people trying to live forever. So this one person that you’re going to see in this scene, Liz Parrish, was the first person to undergo a genetic therapy that has not been approved for humans. It’s only been done on mice.

[Clip Plays]

Liz Parrish:

What would you do if you might be able to save millions of lives with one action, an action that might take your life? What if you had to build a business to do this? Learn a new science. Be judged and treated like a lab rat. Would you do it?

Liz Parrish:

I am three days out from taking two gene therapies. One never performed in a human. I don’t feel well. I can’t sleep. Wake up with my heart pounding. I keep picturing the person who will find me dead. Hopefully, I will live. I am totally happy with my decision either way because, today, all sorts of people are dying, people I know nothing about, but they are just as real as I am. And I am in good company.

Liz Parrish:

I’m okay. Let’s just do it.

[end of Clip]

Jonathan Dowler:

It’s very lyrical, very beautiful. So in terms of what we’ve talked about, finding the stuff, talk about the breakdown of that scene and how you approached it.

Ian Sit:

So it was quite an organic way of cutting. Basically, we went through all the footage and tried to identify the most salient things, and just build from there. What was shot with Liz was a sit-down interview. There was also footage of her just walking around her home, which was that forest, and there was also footage shot of her reading a letter that she was composing while she was undergoing the experiment as a form of personal emotional therapy in case she died. She was trying to write a justification as to why I’m doing this.

Ian Sit:

So when I was going through the footage, the moment where she breaks down, that was kind of like, oh, that’s a good moment. Every time you have someone showing genuine emotion in that way, it feels like it’s probably important. So we started with that, but it occurred to me that the way she was reading the letter sounded a lot more like voiceover than it did just a regular person reading, so we attempted to pair that audio with the footage of her walking around in the forest, which started to create a kind of fairy tale-y, dramatic, narrative scene. Which was an interesting moment.

Ian Sit:

And it could’ve played out that way entirely, but we didn’t want to lose the on camera moment where she started to break down. And so the decision was made to kind of set it up in such a way where she’s kind of walking around in the forest, but then all of a sudden, you cut to her reading the letter, and it became a bit of a dance between these two things.

Ian Sit:

That scene was cut, and it was put aside. At a certain point of cutting the rest of the film, we decided that this would be the very first scene of the entire movie. There are other subjects involved as well, but we liked how it started. So once we moved it to the top, we needed to build a kind of a bit of a tease, a bit of a hook. And that’s when we got the footage from the actual experiment, which we did not shoot. Liz provided for us. And so that was inserted afterwards in order for us to build more of a moment where she-

Jonathan Dowler:

And that’s the button. The button at the end. Let’s do it. Let’s get this done.

Ian Sit:

And I don’t think it would’ve worked if we had just inserted that stuff hadn’t the theme been played out like a dramatic scene without that kind of grounded moment where she’s very emotional, and we see her on camera. So it ultimately kind of came together step by step as we were going through the film.

Jonathan Dowler:

That’s great. Well, I think it’s incredible to see, much like any unscripted, she’s commenting, and we’re seeing what she’s talking about. It’s all on her face, like you say, in the tears.

Jonathan Dowler:

We were talking earlier, saying action is character, but it’s actually reaction. And those looks that can be built, be it in the Jade scene, where it’s the look of the people as they’re watching things, even if they’re talking about lunch.

Jenypher Fisher:

They were really serious about lunch.

Jonathan Dowler:

They looked hungry. And even in Race, it’s those looks of sheer terror, or being ticked off. I think we’re going to go to questions now.

Audience Question:

This is for Baun, but I guess anybody can answer. Just referring to your scene we showed today. You talk about how the original version was 11 minutes and change.

Baun Mah:

Yeah.

Audience Question:

And then you get down to about two and a bit.

Baun Mah:

Yeah.

Audience Question:

I’m assuming your edits aren’t really loose, but do you ever cut assuming I know this is going to be two minutes so I should make it two minutes, or do you always leave it a little bit longer, and let the writers kind of break it down?

Baun Mah:

No, I think the key to doing a show like Race is if you do know, then that’s great. Yeah, cut it down as much as you can. I think in this one, them getting lost is such a … It’s happened before, but it’s such a unique moment in Race that I find it very interesting. And it was also that it did have these moments of tension, so we did leave it in for the rough cut screening just because up until that rough cut, or even our internal screening, we have no idea what the other people are doing yet. Our story editor, Seth, had set up a story board through Trello, so he was updating it daily, but we didn’t know which tension beats would work. At that point, I still hadn’t realized how crazy the foot race at the end … Obviously, you guys don’t know what happened, but it was a long but really exciting foot race to get to the mat. So that was prioritized over this.

Baun Mah:

So, typically, yes, you would try to cut it down to maybe … 11 was way too long, and I put that on me because my cuts to the assembly usually end up being a little longer. But, yeah, it should’ve maybe been around five or six. That’s a little more reasonable, and then you cut it down in half. But really we wanted to see how this played out, and because if we cut it to the two and a half minutes … Like say we did cut it down to the two and a half minutes right away, we might questions like, oh, what happened? How did this team find out, or how did this team get lost? And did anything interesting happen here?

Baun Mah:

So sometimes on Race, it’s like you show what happened, and then once everyone has an idea of what happened, you whittle it down. And then you realize at least you can justify why you cut certain things out. So you present your whole case, and then you just keep the best bits.

Jenypher Fisher:

I personally always know what the times are right from the start, and I’m really annoying with writers because I’ll always tell them what the times are. I will always tell them “We are 10 minutes heavy at the end of the assembly, just so you know. Act One is really long, it’s this long.” If it’s a four act structure, I’ll know how long each act is generally. I’m not annoying about it, but I want everyone to know we’re seven minutes long, so if you have anything you’re not loving, get it out of here.

Jenypher Fisher:

And every time, every cut, I’m always trying to shorten it, because I’ve worked on too many shows where you’re not cognizant of it, and you’ve got an hour-and-20, and it’s just do it from the start. It’s just easier. We call it killing our babies. Like start killing the babies early. Choose a few that you want to protect and love, and then just start whittling it down. It makes it easier in the long run.

Baun Mah:

On the flip side though, we’ve had moments, not necessarily on Race, but on other shows where we do cut it closer to time because we do know roughly what our Act One, Act Two, all the acts should be. But then either the producer or the network or whoever who is not directly involved in the edit, they’re like, “Do we have another moment of this?” Or “Does this moment play out more?” So it’s sort of like a give or take. Then you’re like I would rather cut down rather than rebuild. I always find it’s much easier to compress than it is to open things up again. So I come from that sort of standpoint, where it’s like, okay, let’s show them everything, and then … Not necessarily everything, but what we feel is good, and then you’re like, “Okay, this is what we have,” and then we’ll cut it down after the assembly or the rough cut.

Jenypher Fisher:

Don’t get me wrong, my assemblies are longer. It’s just like I always tell them.

Baun Mah:

Yeah.

Jenypher Fisher:

We’re always going for this.

Baun Mah:

It’s great to be vigilant on that, yeah.